By Joseph Hong

August 13, 2018

Citing a report that showed increased marijuana use by Colorado’s youth immediately following legalization in the state, the Palm Springs Unified School District wants to prevent similar outcomes for its students.

In late May, the district announced a proposal to stifle potentially detrimental effects of cannabis legalization on students and campus climate. The district’s three-pronged strategy includes reassessing school discipline, renewing counseling efforts and a prevention curriculum for parents and students across grade levels.

“If you look over the last three years, we’ve had increases in suspensions and expulsions for drug and alcohol use,” said Anne Kalisek, the district’s director of student support services. “It’s one of the top three reasons we suspend or expel students.”

According to a study funded by the White House, Kalisek said, Colorado saw a “spike” in usage among school-age students following the legalization of cannabis. Since Jan. 1, when California’s law legalizing recreational marijuana for adults went into effect, the district has seen an increase in suspensions for drug-related violations.

From the 2014-2015 to the 2016-2017 school years, the number of suspensions rose from 216 to 298. In the 2017-2018 school year, that number rose to 401 suspensions for possessing, using or selling controlled substances on campus.

While the direct relationship between the trend and the legalization of cannabis is uncertain, the district plans to revise its drug-related discipline protocols to focus more on counseling and prevention.

After the first violation, students will be placed in the Insight curriculum, which will help them set goals and develop self-esteem. A second violation will result in one-on-one counseling through the district’s Bridges program, in which therapists will address the individual needs of the student. The student will be considered for expulsion after the third offense.

Expulsions will be taken on a case-by-case basis in front of the school board and a hearing panel. If a student is expelled, he or she would continue to receive mental health services from the district.

But through a multi-city collaboration, the district hopes to direct its energy toward interventions at the first two violations. The district expects to hire a dedicated substance-abuse counselor by the end of August using funds provided by the cities.

“We hope this dedicated counselor can determine whether this student was just giving in to peer pressure,” Kalisek said. One of the main changes to this protocol will be distinguishing heavy users from those students who may have used cannabis only once or twice.

Before, these two groups were lumped into a single category, Kalisek said.

According to Proposition 64, which passed in 2016 and was implemented at the start of this year, tax revenues from recreational cannabis sales would be dedicated partly to youth education and prevention programs. The district, however, has yet to see this money. To help pay for the staffing and the necessary curriculum, it went to the cities for help.

“It’s great to see PSUSD take the initiative with this program, which provides access to education, treatment and counselors for students and parents,” said Isaiah Hagerman, city manager of Rancho Mirage. “Hopefully, this program can be used as an example for the state for future use of Proposition 64 monies in our schools.”

So far, Rancho Mirage, Cathedral City and Palm Springs have each contributed $100,000 to launching the program. Desert Hot Springs will revisit the district’s proposal early next year during the city’s mid-year fiscal review.

“We do have a definite time frame for when we’re going to revisit that issue,” said Doria Wilms, spokeswoman for Desert Hot Springs. “We absolutely support education, specifically drug education for the youth in the school district.”

Proposals have also been sent to the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians as well as the Desert Healthcare Foundation for consideration.

The funds will cover the salary for two substance abuse counselors, administrative support and a curriculum for students and parents designed by The Courage to Speak Foundation, an organization based in Connecticut.

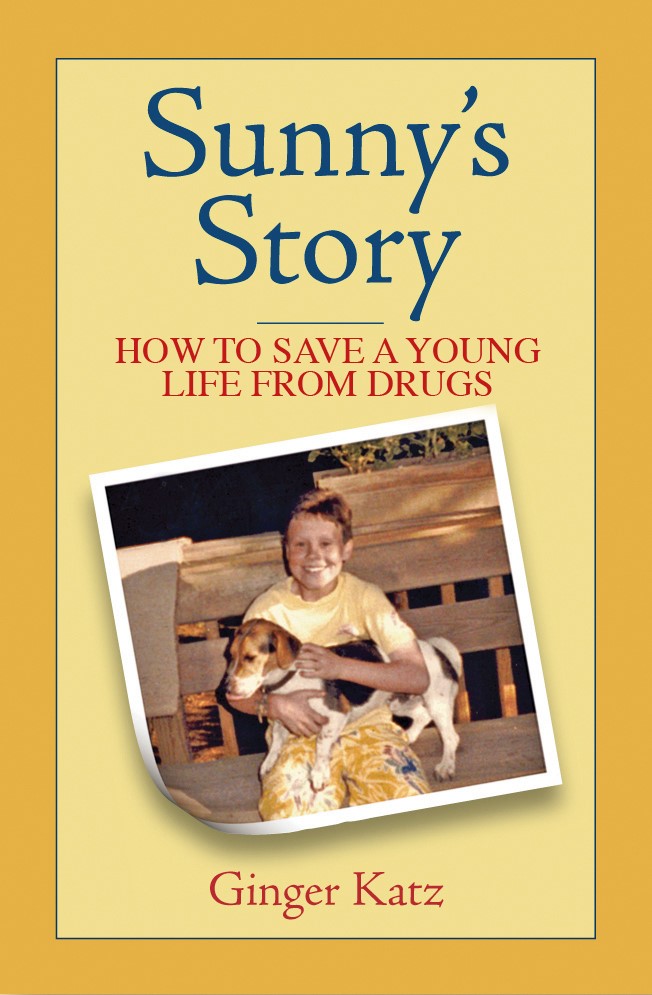

Ginger Katz founded Courage to Speak after her son Ian died as a result of a heroin overdose in 1996. Since then, Katz has designed a holistic educational program for both students and parents and has published a children’s book that helps children understand the impact of drug abuse.

Sunny’s Story is told from the perspective of the Katz family dog, Sunny, who followed and witnessed the effects of Ian’s addiction.

“Sunny’s a silent observer that tells a story without preaching,” Katz said. “If Sunny could’ve talked he would’ve had a lot to say.”

The book has been edited and endorsed by experts in the fields of education and substance-abuse treatment. Courage to Speak’s curriculum focuses on social-emotional learning, emphasizing the importance of self esteem in the face of peer pressure.

The elementary school curriculum will revolve around Sunny’s Story and include scientific demonstrations and writing exercises that will help these younger students develop refusal skills.

The middle school curriculum will be more concrete, helping students develop decision-making strategies and cultivate relationships with three to five trusted adults. High school students will get into the details of specific types of drug abuse. And the parents’ curriculum will provide instruction on navigating the “drug culture” and communicating effectively with children.

“I think it starts with self-esteem, and some kids don’t have it so they’re more at risk,” Katz said. “Let the child talk. If you’re not available for your child, they’re going to be talking to somebody else.”

According to Katz, students need to feel supported in their decision to make healthy choices. Athletics, religious communities and families, Katz said, can give students the confidence to say “no” during those crucial moments.

“All children are at risk. Every child will be asked to smoke this with me or try this pill,” Katz said. “Parents are the key to prevention.”

With the help of the cities’ contributions, the Courage to Speak curriculum has already been purchased by the district and will be implemented in the next several months.

Even before the program launches, Kalisek said there are things parents can do to open a dialogue with their children about cannabis.

“What parents mainly need to do is what they’ve been doing with alcohol for years,” she said. “If they start opening up to you, don’t be shocked. Don’t be angry.”

The communication between parents and their children plays a key role in Courage to Speak’s philosophy of prevention and treatment. Katz said parents need to approach students who are already using with zero judgment.

“Find out why it’s important for them to use something that’s unhealthy for them,” she said. “They’re not bad kids, they’re just making unhealthy decisions.”