By: Tatiana Flowers

November 3, 2018

NORWALK — At 4 a.m. on Sept. 10, 1996, Ginger Katz’s dog climbed four flights of stairs and jumped onto her bed. Sunny woke her up from the best night of sleep she’d had in five months.

The night before, Katz’ son said, “Mom, I want to see a doctor in the morning. I need to take care of my problem.”

Ian Eaccarino, 20, struggled with drug addiction for about seven years, and Katz said his desire to seek treatment is what helped her sleep that night.

When Sunny woke her up, Katz thought nothing of it — and she went back to bed until her morning run at 6 a.m.

Right before she was about to leave, she heard Ian’s TV was louder than normal. She went into his room to check on him and realized why Sunny woke her.

After they talked the night before, Ian went back to his room and did heroin and Valium, the name brand for the prescription drug diazepam.

“At the wake, we were telling people we were waiting for the toxicology report, but we knew,” Katz said.

People didn’t ask, but Katz is convinced others thought he died by suicide.

“I knew the night before the funeral I’d be addressing it and speaking out,” she said. “He was a good kid and I wasn’t ashamed of him — and I refused to bury him with a lie.”

That’s how she ends her Courage to Speak presentations to students in Connecticut and around the country.

“Kids never think he would die at the end of the presentation,” she said. “Kids internalize their pain and the whole philosophy is to share secrets and not keep pain inside.”

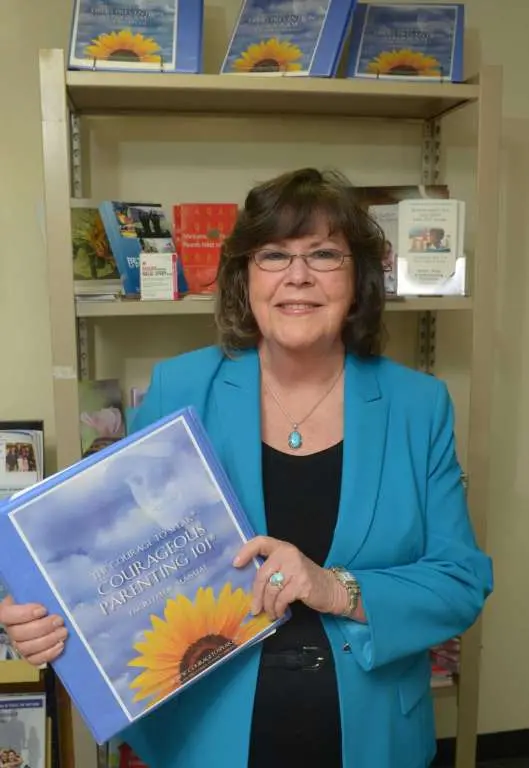

Courage to Speak Foundation is a nonprofit organization run by Katz, two of her staff and a few volunteers. She started by speaking at Norwalk High School, where Iam went to school almost two decades ago.

She continued talking with students in Norwalk and expanded into other parts of Connecticut. Now, with the help of school psychologists, Yale School of Medicine psychiatry staff and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration, she travels nationally to speak to students, parents, teachers and school leaders.

She also crafted a drug prevention curriculum which is embedded into middle and high school health classes in Norwalk and around the country. To date, she’s spoken in 87 Connecticut towns and 30 states, she said.

When students leave her presentations, they understand the stigma and silence around drug addiction and they see the enabling from family members and friends, the desire to get help, relapses, and the overall progression of the disease, she said.

One of the organization’s goals is reaching out to parents through a course called Courage to Speak Courageous Parenting 101. It teaches parents how to keep their children safe by discussing refusal skills, knowing the signs of drug use and facts about marijuana and opioid use. It’s typically a five-session course, but Katz condensed it to one session for an upcoming talk in Norwalk, “Parenting Through the Opioid Crisis and Beyond,” scheduled for 6 p.m. Thursday at West Rocks Middle School. Registration is required.

Lois M. Snelson, a health teacher at Roton Middle School, said sixth-grade students read “Sunny’s Story,” a book by Katz that tells Ian’s story from the dog’s perspective.

As part of her health class, Snelson said she introduces students to the intricacies of drug addiction and the concept of a gateway drug. Cigarettes and marijuana were gateway drugs in the past, but now prescription pills are, she said.

The students in Snelson’s sixth-grade class are also shown a real lung damaged by cigarette smoking, a hard-hitting lesson as visuals have the most impact, she said.

The following school year, the students receive an in-person visit from Katz. She presents for an hour, allowing the seventh-grade students are finally able to put a face to the name, Snelson said.

Some of the students Katz is now reaching out to are the children of Ian’s friends. “If I can help anybody along the way, I will, so they don’t have to suffer what I’ve suffered,” Katz said.

As part of her talk with students, Katz details the chronology of her son’s slide into opioid addiction.

First it was cigarettes, then tobacco, then beer, then marijuana, Katz said.

Freshman year of high school was when police found marijuana in Ian’s car. Around that time, his grades dropped, he was volatile and had a hard time getting up in the morning. This was unusual for him, Katz said, and so she decided to look around his room.

She found nothing suspicious and decided a drug test would be better.

“It was awkward,” she said. “I didn’t want to accuse Ian, but my job as a parent is to keep him safe.”

He took two drug tests, and both were clean.

After he died, one of his friends told Katz the urine must have belonged to someone else and that no one in their circle of friends was clean.

All through high school, however, Ian’s counselor maintained he wasn’t on drugs. “Not only did he fool us, but he fooled the counselor,” Katz said.

Still, Katz said, there were signs, like his car blowing up in the driveway his junior year and setting fire to a nearby tree. Then, in college, he got into an altercation that resulted in him needing 17 stitches.

The dean at the University of Hartford gave him 100 hours of community service and once he completed 36, a resident manager told him that would suffice.

“Enabling perpetuates the disease of addiction,” Katz said. “Don’t underestimate any drug use with your child because it does hijack the brain.”

When Ian died, Katz felt Americans needed education about drug addiction. Nobody was talking about it and she had to piece things together for herself. Following his death, Ian’s friends recounted his darkest secrets and Katz asked for records from the treatment center he attended.

“I was a sharp parent, but kids have secrets,” she said, especially those with this disease.

In order to share her son’s story, Katz relies on financial support from the Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, a family night she hosts in April, and a race held in her son’s name every August. Individual donations and occasional payments from presentations also help the organization, she said.

Katz attributes her ability to heal to an Al-Anon course — its name a take on Alcoholics Anonymous, but the program focuses on family and friends of users. In the course for parents, she learned a slogan: “I didn’t cause it, I couldn’t cure it and I couldn’t control it.”

That idea, Katz said, has helped her heal — even though it still feels like Ian died yesterday.